Is Change Simple?

Change can come about in either a proactive or reactive fashion. In Reactive change situations, something changes, and we're forced to respond (or not, which is another form of response). The Proactive approach is where we decide to initiate change, and set out to implement.

Whether its a proactive or reactive approach has implications for the subsequent process of planning, method, and implementation.

All planned change involves a current present state and a future desired state. Change is the shift, or transition, from one state to the next. Change management is the higher level of change, as it involves the human, personal aspects of a change process.

Change at its most basic this is pretty simple - you just gradually improve things by introducing minor incremental change. Not much change management is required with this basic developmental form of change. It's gradual and incremental...

It's a bit more complex when there is a clear starting and finishing point, with a significant transition - which looks more like this:

In theory, running a 'Change Program' could be as simple as just setting out on the road from the old to new (or Present to Desired) states, and then simply arriving!

On the journey however, there are often challenges and even obstacles. They can include:

- Clearly understanding the starting point and the destination (as this determines the possible routes).

- Selecting the best of the possible routes.

- Knowing what the first steps are, taking those steps, developing momentum, and continuing undistracted.

- Making appropriate choices at decision points along the way (forks in the road).

- Dealing with resistance (headwinds, traffic moving in the other direction, dark tunnels, bridges out).

- Maintaining sufficient momentum (performance from your change management team) along the way (not running out of fuel).

- Keeping a fix on the destination, and moving ahead till you make it.

A good change management program can be of great help with this form of change. Much can be predicted upfront if the right work is put in. Resistance to change can be both from internal (resistance, undermining) and external factors. Particularly with internal resistance, effective change management is essential if yours is to be one of those change programs where the desired state is achieved. And many external factors can be predicted and planned around.

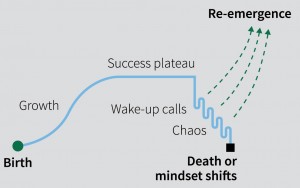

What if it's apparent that change is needed, but the outcomes are unknown?

Or more challenging, if the early signals for change have been ignored, and change is ultimately forced upon the organisation?

If enough change signals (wake-up calls) are ignored, radical transformation may be the only way to avoid succumbing to a slow (or sudden!) demise.

With transformational change, the best change management methods can be frustrated unless you also build change readiness and resilience. These help people into a better state to survive and negotiate the chaos and still be there for the ultimate re-emergence of whatever new form surfaces.

Facts about change

Only around one transformation in three succeeds, according to a survey of executives around the world by McKinsey. Kotter had said much the same way back in 1996, in his seminal book Leading Change. So with many years post-Kotter of experience using internal and external change management support, and hundreds of different approaches to managing change, it's still tough to succeed with change.

Part of the reason for the poor success rate in change initiatives is, not surprisingly, poor ‘Change Management’. This is very much about the human side of a change process. It’s easy enough to develop a technical change program and related process planning documents, but humans are, well, human! This brings into play consideration of the psychological and emotional aspects of change, and without any planning and action around these, success will be even lower than that 1 in 3.

Major change is generally driven by imperatives, often related to one or more of these factors:

- Mergers and acquisitions (acquiring another organisation, or being acquired, and the integration process that has to follow);

- Significant downsizing, or sudden fast growth;

- Substantial new product or service areas, or the loss of old ones;

- Other major responses to changes in the business environment, government policy, or client/customer behaviour;

- Disruptions or innovations in technology or the industry;

- Political or societal disruptions.

Change can be incremental or revolutionary, superficial or deep, temporary or lasting.

And even when the drivers are for change at the organisational level, what’s required usually includes change at the personal level. On this theme, Quinn said that:

“Deep personal change is being demanded with much more frequency today than in the past….Organizations become structured and stagnant, and so do individuals. We have knowledge, values, assumptions, rules, and competencies that make us who we are. As the world around us changes, we lose our sense of alignment and begin to have problems. Often we can resolve these problems by making a small adjustment or an incremental change. Sometimes, however, we need to alter our fundamental assumptions, rules, or paradigms and develop new theories about ourselves and our surrounding environment. When this need emerges, we try to deny or resist it.” (Quinn 1996).

Of course, denial or resistance are just two of many possible responses to change, and often occur early in a change cycle.

It may well be that some people are generally more change friendly, while others are more resistant. We probably all fall somewhere along a change-friendliness continuum:

Our position could be different depending on the type of change - for example, some people might embrace technological change but resist organisational structure or leadership change.

Take a moment and consider - where would you position yourself on the spectrum? Does it vary according to different situations, or are you regularly on one position along the spectrum? And what does it take for you to get on board with a change ... or do you keep on keeping on...!

Models of change

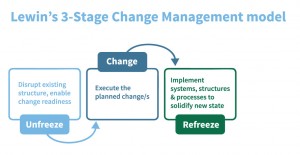

Most models of change are variations or developments of the original three steps: unfreeze, change, and refreeze. This was developed by Kurt Lewin (1890 – 1947) – ‘the father of modern social psychology’. He proposed that change involves three steps: unfreezing the organisation, implementing the change, and refreezing the organisation.

Since then, theorists including Kotter have revised this model to add more sophistication (usually more levels within these 3 levels). You can also challenge the notion of being able to unfreeze an organisation that is in reality somewhat fluid, or wanting to fully 'refreeze' it after a change. But realistically, most organisations are ‘frozen’ by their structures, systems, processes, policies, leadership, culture and so on, and most major changes (even minor ones) require some ‘unsticking’ before things are put back together anew. This is more the case with major change such as mergers, acquisitions or massive downsizing or restructures.

The Change Curve model is also considering in the planning stages. It describes the four stages most people go through as they adjust to change.

People's initial reaction may be shock or denial, as they react to the challenge to the status quo, then they tend to react negatively, fearing the impact; feeling angry; and actively resisting or protesting against the changes - some will wrongly fear the negative consequences of change, while others will correctly identify real threats to their role, team or services. If not carefully managed, the resultant disruption can quickly spiral into chaos. The coming stages of exploration/acceptance and rebuilding/commitment are where the opportunities for success start to be realised.

With the right tools you can more effectively manage change by minimising the damage and accelerating the process. (Get in touch with us for more on our method for managing change using the Change Curve framework).

In “The psychology of change management”, Emily Lawson and Colin Price suggest that four conditions are necessary before employees will change their behavior:

- a compelling story, because employees must see the point of the change and agree with it;

- role modeling, because they must also see the CEO and colleagues they admire behaving in the new way;

- reinforcing mechanisms, because systems, processes, and incentives must be in line with the new behavior; and

- capability building, because employees must have the skills required to make the desired changes.

It takes both positive and negative motivators to drive lasting change.

It has become traditional to use a “deficit based” approach—which identifies the problem, analyses what’s wrong and how to fix it, plans, and then takes action— as the default change model in most organisations.

However, a story focused purely on what’s wrong, while it paints the picture about the need for change, also invokes emotive responses and blame, can create fatigue and resistance, and does little to engage people’s passion and experience.

On the other hand, a purely positive rationale for a change program (discovery, dreaming, design, and destiny as in the ‘constructionist’ approach) misses impact as it is often unrealistic, and lacks a strong emotional driver – a ‘must’. The ideal approach is often a mix of ‘what’s wrong?’ and ‘what might we create?’.

Change and control

We kid ourselves: Just as 94% of men rank themselves in the top half according to male athletic ability (obviously statistically impossible, only 50% can be in the top half), most of us don’t count ourselves among those who might need to change. On average, we humans consistently think we're better than we are - a phenomenon referred to in psychology as a self-serving bias. We also mistakenly often over-estimate our ability to control outcomes (of course there are natural 'under-estimators' too).

We like to be a part of it: Speaking of control, people are more committed to change if they are a part of making it happen. A famous experiment by Langer, replicated by other researchers, involves a lottery. People are either given tickets at random or allowed to choose their own. They can then trade their tickets for others hoping for a higher chance of a payout. People who had chosen their own ticket were more reluctant to part with it. Tickets bearing familiar symbols were less likely to be exchanged than others with unfamiliar symbols. Although these lotteries were random, people behaved as though through their choice of ticket they could positively affect the outcome. Participants who chose their own numbers were less likely to trade their ticket even for one in a game with better odds! What this means for a change program to have the best shot at success is that while leaders should provide a compelling change story, it’s also important that anyone in the organisation can contribute their own part of the story.

Resistance To Change: One of the most well-documented findings about change is that organisations and their members tend to resist it. While this is natural, it hinders adaptation and progress. Resistance to change surfaces in many ways. It can be overt, implicit, immediate, or deferred. It is easier to deal with resistance when it’s overt and immediate.

Implicit resistance efforts are more subtle - loss of loyalty to the organisation, loss of motivation, increased errors or mistakes, increased absenteeism as well as presenteeism (people being in the workplace but with little commitment and low engagement) - and hence more difficult to recognise.

Deferred resistance clouds the link between the change and the reaction to it - there may be only a minimal reaction at the time change is initiated, but then resistance surfaces weeks, months, or years later. Reactions to change can build up and then explode seemingly right out of proportion. In this case the resistance was deferred and stockpiled, and what surfaces is an accumulated response, making it harder to deal with and more emotionally charged than it would have been if picked up earlier).

There are many reasons based in cultural, group and personal psychology as well as organisational culture as to how we respond to change and why resistance can happen. It can be important to know these, and more important to know how to overcome the resistance. We can bring understanding of resistance and strategies to deal with it to any change management assignment, to give our clients the best shot at a positive transition to the new.

Leaders in change

Adding structure and certainty: Adding some certainty in a time of uncertainty is a reassuring behaviour that leaders can demonstrate.

Providing staff with structured change management programs including timelines and the like are great ways to demonstrate that ‘we are in charge’, and this is somewhat reassuring to most of us even if at times it's only partly the case!

The sense of certainty or comfort helps focus people’s efforts and reduce uncertainty and fear in times of change, and we are typically more productive if we come from this sort of place.

Change and performance

The importance of setting aspirations that emphasise ‘organisational health’ (the human aspects) as well as ‘performance’ in designing change initiatives became very apparent in a McKinsey survey: change programs with well-defined aspirations for both areas were 4.4 times more likely to be rated extremely successful than those with clear aspirations for performance alone.

The ‘soft stuff’ is often overlooked in change initiatives, but it’s critical. A related study found that when senior executives had implemented initiatives to change their employees’ mind-sets and behavior during a transformation, the executives were twice as likely to report that the initiatives had succeeded.

Three keys to successful change programs

There are three major common factors in successful transformations. These are engaging employees collaboratively, building capabilities, and focussing on strengths and achievements, and not just problems (findings in a 2010 McKinsey Global Survey that's still relevant now).

- Engaging employees collaboratively throughout the company and throughout the transformation journey.

- Building capabilities—particularly leadership capabilities—to maintain long-term organizational health.

- Focussing on strengths and achievements, not just problems, throughout the entire transformation process.

Bringing Atwork into the process early will help ensure that your change program is based around these three key success factors. And if you bring us in later, we'll still come in to support your organisation with our successful approach, based around a strong understanding of change concepts and effective, practical implementation that best positions you for ultimate success.

How we help with Change

We're often called on to help clients manage change within their organisations. We bring a framework based on the concepts outlined above - but we're flexible, and we design our approach to fit your organisation's needs, people and culture. This is more powerful than just coming in with any one fixed change metbodology. Why not use the approach that gets the best outcomes?

For more information, head through to our services in Organisations - Consulting and Leaders & Teams - Growth Programs